What is Gabor‑Granger?

Gabor Granger is a pricing research method that asks customers yes/no questions at a series of price points for a single product.

At each step:

- Show a product at Price A → “Would you buy this?”

- If “yes,” increase the price → ask again.

- If “no,” decrease the price → ask again.

- Repeat until a ceiling is found.

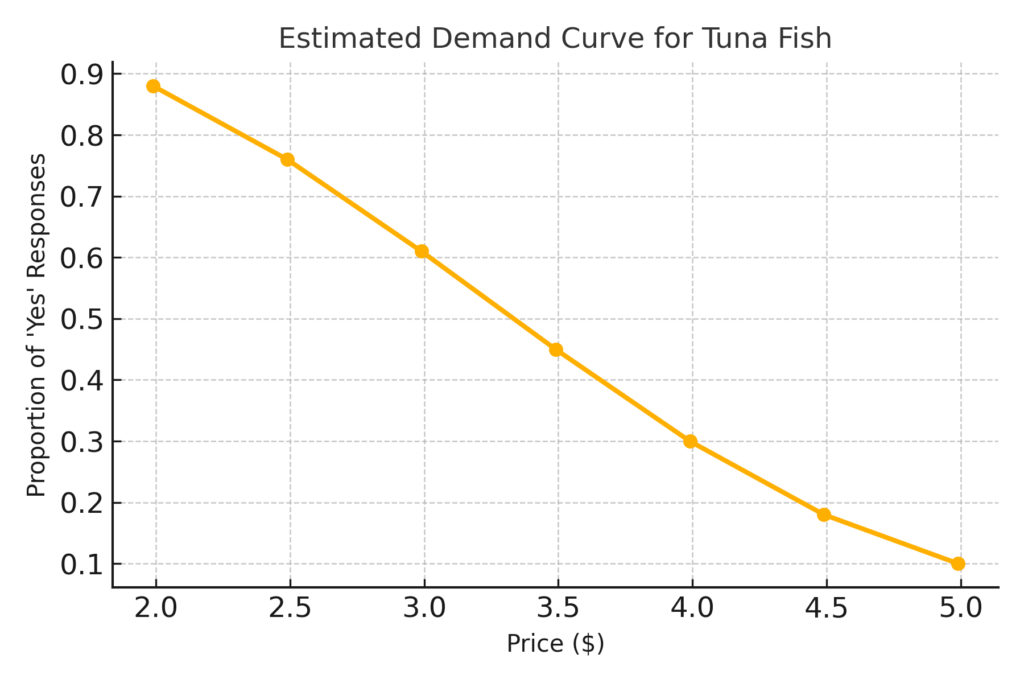

This produces a simple demand curve from “yes” answers.

What the Method Produces

The output is a demand curve — showing the proportion of “yes” answers at each price — and a derived revenue curve based on multiplying demand by price.

From this, it identifies the “optimal” price (i.e., the one maximizing revenue).

If the demand curve is to be believed, revenue is easy to calculate.

But there are many reasons not to believe it.

The Limited Value It Brings

It’s simple. It’s fast. And the results are easy to communicate.

But that simplicity hides real risks:

- No competitive or real-world context

- Artificial behavior in the task

- A dangerous illusion of precision

This isn’t a model of behavior — it’s a quiz about a hypothetical.

The Five Critical Flaws

These aren’t minor gaps — they fundamentally distort the findings.

- The Demand Curve Illusion

Looks rigorous, but it’s just a guess without context. - Price Without a Shelf Isn’t Price

People don’t choose in a vacuum — but GG assumes they do. - You Don’t Buy Like This — So Why Ask This Way?

It’s unrealistic — nobody shops in a yes/no loop. - Built to Be Gamable — And That’s the Problem

Respondents quickly learn how to game it — and they do. - When Budget Shrinks, Gabor Granger Magically Becomes Good Enough

Chosen for cost, not merit — which says more about us than the method.

Each flaw has its own writeup— click to explore.

Why It Still Gets Used After “Real” Methods Get Cut

Because it’s:

- Cheap

- Familiar

- “Good enough” when no one’s paying attention

It’s not chosen for its fit — it’s recommended when better options get rejected.

Although first introduced in 1966 (Gabor & Granger, Economica), the method remains in use — often as a low‑budget fallback.

If you’re just trying to spend leftover budget… fine.

But don’t call that strategy.

What Real Price Decisions Require

If you’re setting prices that affect:

- Profit

- Forecasts

- Product hierarchy

- Channel strategy

…you need a method that ties to the income statement — not just survey charts.

How to Know If Some Pricing Research Is Enough

Ask:

- Are you pricing a simple product in isolation?

- Is this just a placeholder until a better method is funded?

- Will people make real decisions from the output?

- Will leadership expect it to reflect reality?

- Is the team likely to over-trust the output?

If the answer to that last one is “yes,” you can’t afford the wrong method — no matter how cheap it is.

You need a model that connects to your future income statement.